(Subtitle: In which Chris discovers his favorite Broadway stage, suddenly has a revelation about lighting design, and is totally awed by an intricately-detailed set)

Welcome back to part two of my ongoing series, Adventures on Broadway. Today, we will look at the Broadway smash revival of South Pacific, the classic Rodgers & Hammerstein musical currently playing at the Vivian Beaumont Theatre at Lincoln Center. I suppose then, that is as good a place to start as any – discussing the theatre itself.

Setting: Vivian Beaumont Theatre

I think it’s fairly well known that I’m a passionate fan of the thrust theatre. In my mind, it gives you the best of both worlds – the ability to work with sets in a pseudo-proscenium style, while forcing you to work in some semblance of realism as theatre in the round (or in this case, 3/4 round) does.

So imagine my amazement when I get to see the theatre at the Vivian Beaumont. Not only is it a thrust stage, but it’s a deep thrust – there is essentially a full proscenium-style stage that just happens to jut out into the audience, thrust-style (as opposed to some thrust stages which either completely forgo the fly house or only make space for a few feet of battens).

It was love at first sight.

The flexibility afforded by this type of arrangement is incredibly useful, especially for a show like South Pacific that involves a number of different locations. Without a full fly house supporting all those scenic elements the designers of South Pacific simply couldn’t use have achieved what they did.

Summary: I really like the thrust style, I think the Vivian Beaumont is an amazing space (which I will break down in further detail in a moment), and let’s move on.

In Which Detail Amazes Me

On Twitter a few days ago (you should follow @tdsquared on Twitter!) our professor Lynne Koscielniak posted this regarding a scenic construction project she’s working on:

Striving for Lincoln Center quality visuals. – Lynne Koscielniak on Twitter

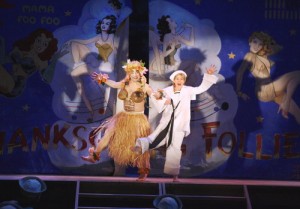

A truck being used for the "Thanksgiving Follies" sequence. Recovered from the junk pile and restored. Sara Krulwich, NY Times

After seeing South Pacific, I definitely know what she’s talking about! Michael Yeargan’s brilliant scenic design itself could be discussed in a post of its own, but the scenic construction completely blew me away on its own right and I felt deserved particular attention this time.

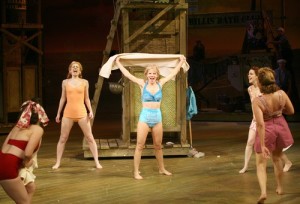

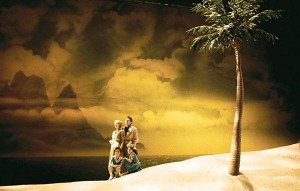

As I mentioned before, the show deals with many scene changes. And as I also mentioned before, they were working with a sort of hybrid proscenium/thrust combination. For this show, that meant there were a fair share of flats, but also a number of three dimensional pieces (either in front of the proscenium or behind it). Taking advantage of the size of the stage, the set featured a larger-than-life palm tree, a full stage sand dune, a 1:1 scale half of an airplane (and rotating propellers), and those were just in one scene.

Of course, these larger-than-life toys weren’t the only things on the set, and in some respects, they weren’t even the most impressive. Some of the coolest elements were for Luther Billis’ various enterprises, including his laundry and his shower business. The laundry unit was constantly moving around during his scenes, shaking around the tub that was holding all the dirty clothes. It looked like exactly what it was supposed to – a hacked up machine from old parts lying around the seabee camp. Of course, it is more likely than not an incredibly intricately engineered device, but it had character that made it feel very appropriate for the setting.

Similarly, the showers had the homemade feel. And like the laundry, they had actual working action! These actually had water come out of them, through an elaborate effect involving waterproof wireless mics, special shampoo, and all sorts of craziness. Awesome stuff.

Of course, there were other more classic settings, such as Emile de Becque’s home. There were a series of flats in layers, designed to evoke the outdoor open terrace where many of those scenes take place. Open doors lead out into the dunes beyond (the dune and palm tree were immovable due to their size, and the designer brilliantly used them throughout). The wall was ornamented with practicals that cleverly helped evoke the time of day. Their slow fade up made it easier to understand where we were in the narrative, and added to the realism of the scene again.

Downstage of those doors were hanging vines, clinging to the furthest downstage set of slats. The slats were used throughout the show, not only acting as a purely scenic element in this scene (and prominently dominating in Bali H’ai) but also masking off the wings from the audience.

What was most amazing about all of these was the quality of the build. The attention to detail was incredibly apparent, and in spite of the scale, the folks at Lincoln Center obviously knew what they were doing as they assembled these pieces and parts. Even from my spot in the loge, I could clearly see the fantastic painting, physical flourishes, and other amazing details. Our friends at Live Design did an article in their “Problems & Solutions” section that addresses some of these elements, explaining how much work truly went into them and the efforts that they had to undergo to solve various problems.

Summary: a larger-than-life set, with amazing attention to the smallest detail. These are craftspeople of the highest order. Good job crew!

I suddenly understand lighting design

One of my biggest revelations during South Pacific involved lighting design. Though I have always considered myself a lighting and scenic designer, in actuality I tend to lean in the scenic design direction. South Pacific may have successfully re-balanced that though; the lighting in this show was stunning in a way that I have never experienced before. Donald Holder’s design balanced a real portrayal with an idyllic artistic portrayal in a way that fused these two competing halves and pushed them to new heights.

Interestingly, it was the floor that tipped me off to this stunning design. The stage of this show is designed in a hardwood floor pattern (real or fake? I couldn’t tell from my seat!) in a light color, presumably a maple or something similar. But Holder’s design brilliantly uses this floor in a way that enables it to meld with the scenario. When we’re outside on the beach, the maple color shines brightly, and it takes on all the colors and characteristics of sand. When we move to Emile de Becque’s terrace, a textured and multicolored appearance takes over, suggesting a tile floor of some sort. And as we enter the office of the captain, the wood floor simply acts as that – purely a wood floor.

Seems simple, right? It probably is – but the way that floor was so well lit that it actually became other materials in my mind simply stunned me, and had me looking for more lighting throughout the show. I began to notice that the lighting had a distinctly stylized tone, but something I would consider a stylized realism. Holder’s lighting gives us a snapshot of how we imagine the South Pacific to be – beautiful, serene, and kinda sexy, but he is not afraid to show us the darker side when it comes time for war. It’s a beautiful island paradise, absolutely, but our problems still follow us there, and we have to face them.

Even when we clearly see the more stylized elements of the show (the War Room comes to mind) it’s grounded in very real elements. Despite these carefully focused lights, they still evoke the dimly lit depths of a barracks, where only a few lights hang over the individual desks to provide just enough illumination for work. It’s blatantly stylized, but grounded in reality. This stylization takes the harsh, shadowed lighting that would exist in the real situation and pushes it to an extreme.

One particular area where “real realism” takes the lead over “stylized realism” is in the Thanksgiving Follies sequence (Act Two opener). The aforementioned trucks quite brilliantly serve as a stage, with very simple lighting befitting of a situation like this – a pair of actor-driven follow spots.

The lighting for South Pacific completely changed my perception of lighting design. Seeing this intricate design, and the way Mr. Holder played with the balance between reality and stylization helped me understand that lighting is simply more than making this visible or not – it actually can contribute to the tone of the piece in new and exciting ways. Although I was already aware of this from lighting class and previous lighting design excursions, I had always taken it to granted, to a degree. South Pacific actually made this idea tangible to me in a way no show has before.

Of course, I think it bears saying that I don’t believe the lighting design truly would not have been as successful without the scenic design – the two wove together to create a beautifully unified environment. Whether it was the moody shadows on the sand dune, the practicals on the de Becque terrace combining with a wash to indicate time of day, or the brilliant dual scrim and backdrop that could be lit to define atmosphere (natural or otherworldly), these two separate design elements work so beautifully together that I definitely question how well they would work separated.

This design is undoubtedly one of the most brilliant that I’ve seen on Broadway, in a venue I certainly hope to work in someday. The attention to intricate details while still maintaining a massive scale elevated this design above and beyond any Broadway show I had seen previously. For design alone, this show is highly recommended. Add in the stellar direction and a top-notch cast and you have a must-see Broadway show. Take the 1 train up to Lincoln Center and be sure to catch South Pacific.

The Details

South Pacific at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theatre

Lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II

Music by Richard Rodgers

Book by Oscar Hammerstein II and Joshua Logan

Directed by Bartlett Sher

Scenic Design by Michael Yeargan

Lighting Design by Donald Holder

Costume Design by Catherine Zuber

Sound Design by Scott Lehrer

The run is open-ended.